Jacquard Fabric History

Jacquard machine

Jacquard Fabric is a highly textured fabric with patterns that are woven, rather than printed into the fabric. Jacquard Fabrics have a raised pattern design

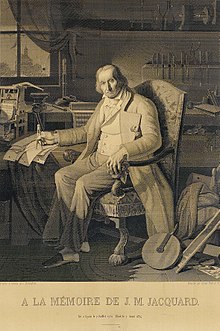

Joseph Marie Charles dit (called or nicknamed) Jacquard (French: July 1752 – 7 August 1834) was a French weaver and merchant. He played an important role in the development of the earliest programmable loom (the "Jacquard loom"), which in turn played an important role in the development of other programmable machines, such as an early version of digital compiler used by IBM to develop the modern day computer.

The Jacquard Loom is a mechanical loom that uses pasteboard cards with punched holes, each card corresponding to one row of the design. Multiple rows of holes are punched in the cards and the many cards that compose the design of the textile are strung together in order. It is based on earlier inventions by the Frenchmen Basile Bouchon (1725), Jean-Baptiste Falcon (1728) and Jacques Vaucanson (1740).

To understand the Jacquard loom, some basic knowledge of weaving is necessary. Parallel threads (the “warp”) are stretched across a rectangular frame (the "loom"). For plain cloth, every other warp thread is raised. Another thread (the “weft thread”) is then passed (at a right angle to the warp) through the space (the “shed”) between the lower and the upper warp threads. Then the raised warp threads are lowered, the alternate warp threads are raised, and the weft thread is passed through the shed in the opposite direction. With hundreds of such cycles, the cloth is gradually created.

This portrait of Jacquard was woven in silk on a Jacquard loom and required 24,000 punched cards to create (1839). It was only produced to order. One of these portraits in the possession of Charles Babbage inspired him in using perforated cards in his analytical engine. It is in the collection of the Science Museum in London, England.

By raising different (not just alternate) warp threads and using colored threads in the weft, the texture, color, design, and pattern can be varied to create varied and highly desirable fabrics. Weaving elaborate patterns or designs manually is a slow, complicated procedure subject to error. Jacquard's loom was intended to automate this process.

Jacquard was not the first to try to automate the process of weaving. In 1725 Basile Bouchon invented an attachment for draw looms which used a broad strip of punched paper to select the warp threads that would be raised during weaving. Specifically, Bouchon's innovation involved a row of hooks. The curved portion of each hook snagged a string that could raise one of the warp threads, whereas the straight portion of each hook pressed against the punched paper, which was draped around a perforated cylinder. Whenever the hook pressed against the solid paper, pushing the cylinder forward would raise the corresponding warp thread; whereas whenever the hook met a hole in the paper, pushing the cylinder forward would allow the hook to slip inside the cylinder and the corresponding warp thread would not be raised. Bouchon's loom was unsuccessful because it could handle only a modest number of warp threads.

By 1737, a master silk weaver of Lyon, Jean Falcon, had increased the number of warp threads that the loom could handle automatically. He developed an attachment for looms in which Bouchon's paper strip was replaced by a chain of punched cards, which could deflect multiple rows of hooks simultaneously. Like Bouchon, Falcon used a “cylinder” (actually, a four-sided perforated tube) to hold each card in place while it was pressed against the rows of hooks. His loom was modestly successful; about 40 such looms had been sold by 1762.

In 1741, Jacques de Vaucanson, a French inventor who designed and built automated mechanical toys, was appointed inspector of silk factories. Between 1747 and 1750, he tried to automate Bouchon's mechanism. In Vaucanson's mechanism, the hooks that were to lift the warp threads were selected by long pins or "needles", which were pressed against a sheet of punched paper that was draped around a perforated cylinder. Specifically, each hook passed at a right angle through an eyelet of a needle. When the cylinder was pressed against the array of needles, some of the needles, pressing against solid paper, would move forward, which in turn would tilt the corresponding hooks. The hooks that were tilted would not be raised, so the warp threads that were snagged by those hooks would remain in place; however, the hooks that were not tilted, would be raised, and the warp threads that were snagged by those hooks would also be raised. By placing his mechanism above the loom, Vaucanson eliminated the complicated system of weights and cords (tail cords, simple, pulley box, etc.) that had been used to select which warp threads were to be raised during weaving. Vaucanson also added a ratchet mechanism to advance the punched paper each time that the cylinder was pushed against the row of hooks. However, Vaucanson's loom was not successful, probably because, like Bouchon's mechanism, it could not control enough warp threads to make sufficiently elaborate patterns to justify the cost of the mechanism.

To stimulate the French textile industry, which was competing with Britain's industrialized industry, Napoleon Bonaparte placed large orders for Lyon's silk, starting in 1802. In 1804, at the urging of Lyon silk merchant Gabriel Detilleu, Jacquard studied Vaucanson's loom, which was stored at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in Paris. By 1805 Jacquard had eliminated the paper strip from Vaucanson's mechanism and returned to using Falcon's chain of punched cards.

The potential of Jacquard's loom was immediately recognized. On April 12, 1805, Emperor Napoleon and Empress Josephine visited Lyon and viewed Jacquard's new loom. On April 15, 1805, the emperor granted the patent for Jacquard's loom to the city of Lyon. In return, Jacquard received a lifelong pension of 3,000 francs; furthermore, he received a royalty of 50 francs for each loom that was bought and used during the period from 1805 to 1811.

dear friend …i am asif khan my working in weaving textile in since.24 years.inpakistan and uzbekistan…00923112439118

Leave a comment